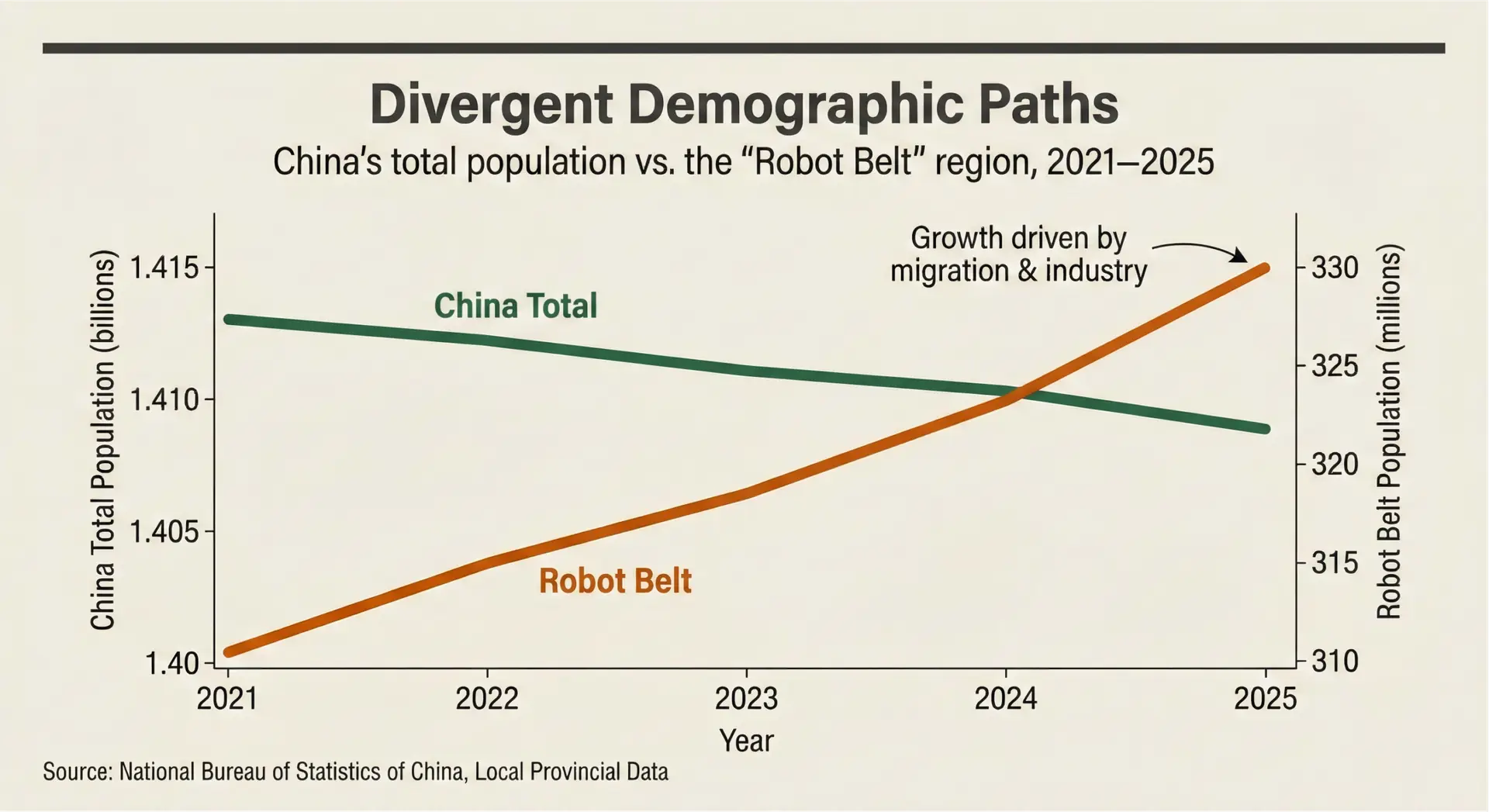

IF DEMOGRAPHY IS DESTINY, then the recent headlines from Beijing read like a eulogy. China’s population has fallen for two consecutive years, shedding millions of citizens in a statistical retreat that Western observers often mistake for an economic surrender. The logic is seductive in its simplicity: fewer workers mean lower growth, collapsing pensions, and the end of the “Chinese Miracle.” In Tokyo and Seoul, where empty cradles have long heralded economic stagnation, the view is one of grim vindication.

But to view China through the lens of national averages is to look at a map through a straw. A closer inspection of the country’s industrial anatomy reveals a different reality. While the vast hinterlands of the north and west are indeed emptying, a specific economic corridor—what might be called the “Robot Belt“—is defying the gravity of decline. Stretching from the Yangtze River Delta in the north to the Pearl River Delta in the south, this coastal strip is not only absorbing the country’s remaining youth through migration; it is actively constructing the workforce of the future from silicon and steel.

The Robot Belt—encompassing Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangdong, and the technological fortresses of Taiwan and Hong Kong—is undergoing a transformation that has no historical precedent. In other ageing Asian tigers, such as Japan and South Korea, the decline in human labour was met with a scramble to import workers or a slow, polite stagnation. China is attempting something more radical.

Consider the numbers. While China’s national population contracts, the population of Zhejiang province, the “muscle” of this new industrial organism, grew by over a million people in the last three years. Guangdong, the “hands” of the global supply chain, continues to swell. This internal migration is essentially a distilling process, concentrating the country’s most productive human capital into a region that produces over 90% of the world’s logic chips (via Taiwan) and dominates the global supply of servo motors and lithium batteries.

While the national headcount recedes, the south-eastern industrial corridor absorbs the country’s remaining youth. Migration to this “Robot Belt” is creating a demographic decoupling, concentrating labour where it is needed most to build the machines that will replace it.

Crucially, this region is not merely using robots; it is birthing them. In the cavernous factories of Dongguan and Suzhou, the “lights-out” manufacturing floor is moving from concept to standard practice. Unlike the Rust Belt of America, which lost workers to foreign competition, the Robot Belt is shedding workers to its own inventions. The region’s 50 top-tier AI universities—nearly a fifth of the global elite—are feeding an ecosystem where the line between a factory worker and a factory machine is dissolving.

This changes the calculus of “Does it matter?” For a service economy like America’s, a shrinking population is a crisis of consumption. But for a production superpower, a shrinking population is merely an efficiency incentive, provided you can build automations faster than you lose humans. China’s Robot Belt is arguably the only place on Earth with the “full-stack sovereignty” to pull this off—controlling everything from the lithium in the battery to the algorithm in the brain.

The pessimists are right that China is getting old. But they are missing the point. The relevant metric for the 21st century is not the number of citizens, but the number of units of production. In the Robot Belt, that number is skyrocketing. The dragon is not shrinking; it is shedding its skin for a suit of armour.