Why Australia’s free market is becoming the ultimate laboratory for Chinese manufacturing.

If you want to see the future of the global car market, do not look to the protected fiefdoms of Europe or the tariff-walled fortresses of North America. Look, instead, to the bottom of the world.

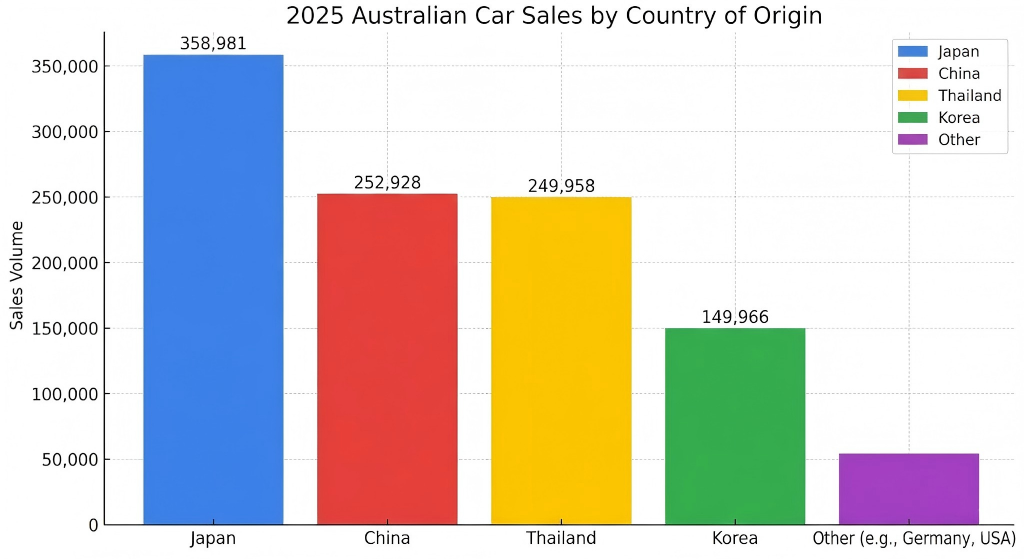

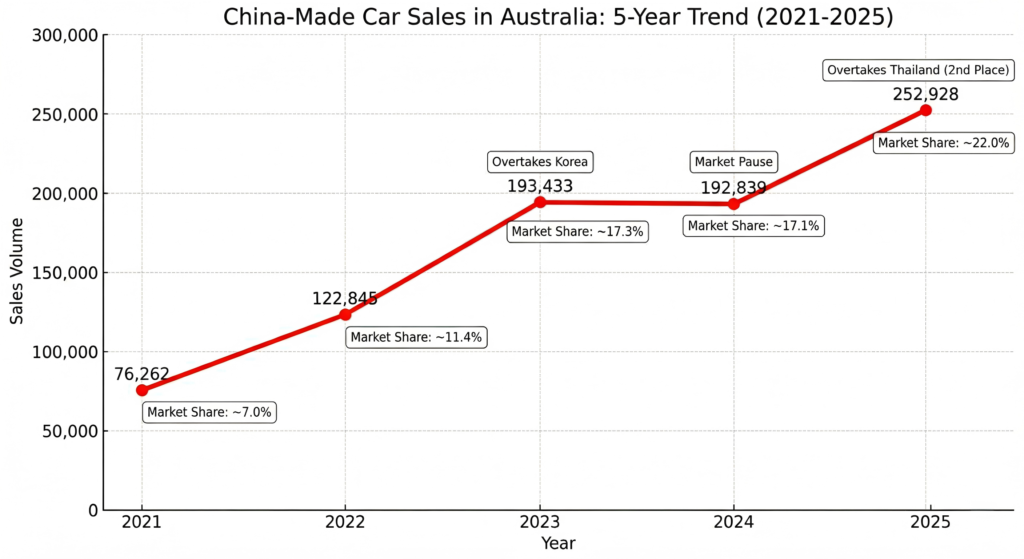

In 2025, a quiet but seismic shift occurred on the streets of Sydney and Melbourne. For the first time, Chinese-made vehicles overtook those from Thailand to become the second-most popular source of cars in Australia, sitting only behind Japan. This ascent, a five-year climb from statistical obscurity to market ubiquity, is not merely a sales triumph. It represents something far more significant: a verdict delivered by one of the world’s purest free markets.

Australia is a unique petri dish for the global automotive industry. Having ceased local manufacturing in 2017, the country has no domestic champions to protect. Every car sold—whether a Ford, a Toyota, or a BYD—arrives by sea. The tyranny of distance acts as the great equaliser; shipping costs are comparable for all players, and there are no land-border advantages for neighbours. In this vacuum of local sentiment and logistical handicaps, the “Australian Test” reveals the raw competitiveness of a brand.

The results are telling. The recent success of Chinese automakers in Australia serves as the best sample of their competitiveness in a near-perfect free market. Under these conditions, legacy advantages—specifically “brand premiums”—evaporate quickly. For decades, Japanese hegemony in Australia was built on a reputation for reliability, fuel efficiency, and low maintenance costs. Yet, this premium was always functional rather than emotional. Chinese manufacturers have now proven they can match or exceed these metrics, often at a lower price point and with superior technology. In a market stripped of nostalgia, where value is the only currency, the Japanese brand premium has effectively died. The displacement of Japanese dominance by Chinese brands is no longer a possibility; it is a matter of time.

This shift offers a provocative lesson for policymakers in Canberra. A decade ago, the Australian auto industry died a slow death, strangled by high labour costs and low efficiency relative to its Asian neighbours. But the automotive sector of the 2020s bears little resemblance to that of the 2010s. The manufacturing hubs of coastal China have transformed car making from a labour-intensive grind into a branch of the robotics and artificial intelligence revolution.

This technological leap changes the calculus for Australian manufacturing. High automation negates the disadvantage of expensive Australian labour. If the factory floor is run by algorithms and robotic arms, the wage gap between a worker in Guangdong and a worker in Geelong becomes negligible. Furthermore, Australia possesses a distinct advantage in land costs. In a vast continent with sparse population density, the cost of industrial land can be driven down to levels competitive with, or even lower than, industrial zones in Asia.

Consequently, the Australian government would be wise to reconsider its industrial policy. Offering tax incentives or R&D subsidies to attract Chinese manufacturers is not about reviving a corpse; it is about buying into the AI & robotic revolution. There is a profound economic symbiosis waiting to be unlocked. The steel in a Chinese chassis begins as iron ore in the Pilbara; the lithium in its battery is dug from Western Australian rock. Even the AI chips driving these vehicles rely on copper and gold, resources Australia has in abundance.

Beyond raw dirt, Australia supplies the brains. Australian-educated researchers are disproportionately represented in the leading AI teams of both China and the United States, punching far above the nation’s weight in scientific output. From mineral resources to human capital, Australia is already underpinning the leapfrog development of the Chinese auto industry. It is only logical to formalise this relationship.

Closer commercial and technical cooperation with China could significantly boost Australia’s own technological competitiveness. Even if Australia does not become a primary hub for assembling right-hand-drive vehicles, becoming a centre for R&D is a tangible prize. Consider the “Ute” (utility vehicle), an Australian invention and a national obsession. Why shouldn’t BYD or Great Wall Motor locate their global R&D centres for electric trucks in Australia? The country’s harsh, diverse terrain and climate offer the ultimate proving ground for rugged vehicles.

Such a partnership would be astute, trading the nostalgia of 20th-century assembly lines for the engineering frontiers of the 21st. It is now a safe wager that the first real-life Transformer—the mechanical giant, not just the language model—will be forged in the Robot Belt of coastal China. Yet, with deep enough integration, the view from Down Under offers a sporting chance: that when such a machine finally greets the world, it might just do so with a familiar, laconic drawl: “G’day, mate.”