In the global arms race for Artificial Intelligence dominance, the headlines are predictable. The United States and China are the titans, trading blows in a high-stakes duel of silicon and software. But look past the giants, scan the data from the 2025-2026 U.S. News & World Report rankings, and you will find an anomaly. It is not in Europe, and it is not in Japan.

It is in Australia.

For a nation of 27 million—roughly the population of Texas—Australia is punching so far above its weight in AI research that it defies statistical gravity. Yet, despite sitting on a goldmine of intellectual property, the country risks becoming a cautionary tale of squandered potential, hamstrung by a government asleep at the wheel and a stock market addicted to the “old economy.”

The Quiet Achievers

The latest U.S. News & World Report Best Global Universities for Artificial Intelligence rankings tell a startling story (U.S. News & World Report, 2025-2026). While China occupies the top spots with Tsinghua University (#1) and University of Science & Technology of China, CAS (#4), the Australian presence in the upper echelon is disproportionately massive.

The University of Technology Sydney (UTS) sits at a staggering #5 globally, beating out all Ivy League institution in the United States. It is not an outlier. The University of Sydney follows at #18, and the University of Adelaide at #20.

This is not a sudden fluke. As early as 2020, research from the Software Policy & Research Institute (SPRi) identified this trend, noting that Australian universities were already performing well above the global average in “Field-Weighted Citation Impact”—a key metric of research quality. The SPRi report presciently placed UTS in the top 10 globally five years ago, proving that Australia’s rise is the result of a decade-long commitment to fundamental computer science research.

By the time you scroll down to the Top 100, the Australian footprint is undeniable: Monash University (#32), UNSW (#71), and Swinburne University of Technology (#88) all make the cut. In terms of high-impact AI research per capita, Australia is arguably the world leader.

The Commercial Unicorns

This academic ferocity has birthed a new breed of commercial titans that are integrating AI with aggressive speed.

Canva, the Sydney-based design decacorn, has ceased to be just a graphic design tool; it is arguably one of the world’s most widely used consumer AI platforms. Its “Magic Studio” suite is a direct challenge to Adobe, democratizing generative AI for the masses. Airwallex, another Australian-born unicorn, is silently revolutionizing global finance, leveraging machine learning to detect fraud and optimize currency corridors in real-time.

These companies prove that Australian soil can grow global tech giants. They are agile, innovative, and increasingly AI-first. But here lies the paradox: they are succeeding despite the Australian ecosystem, not because of it.

The “Valley of Death”

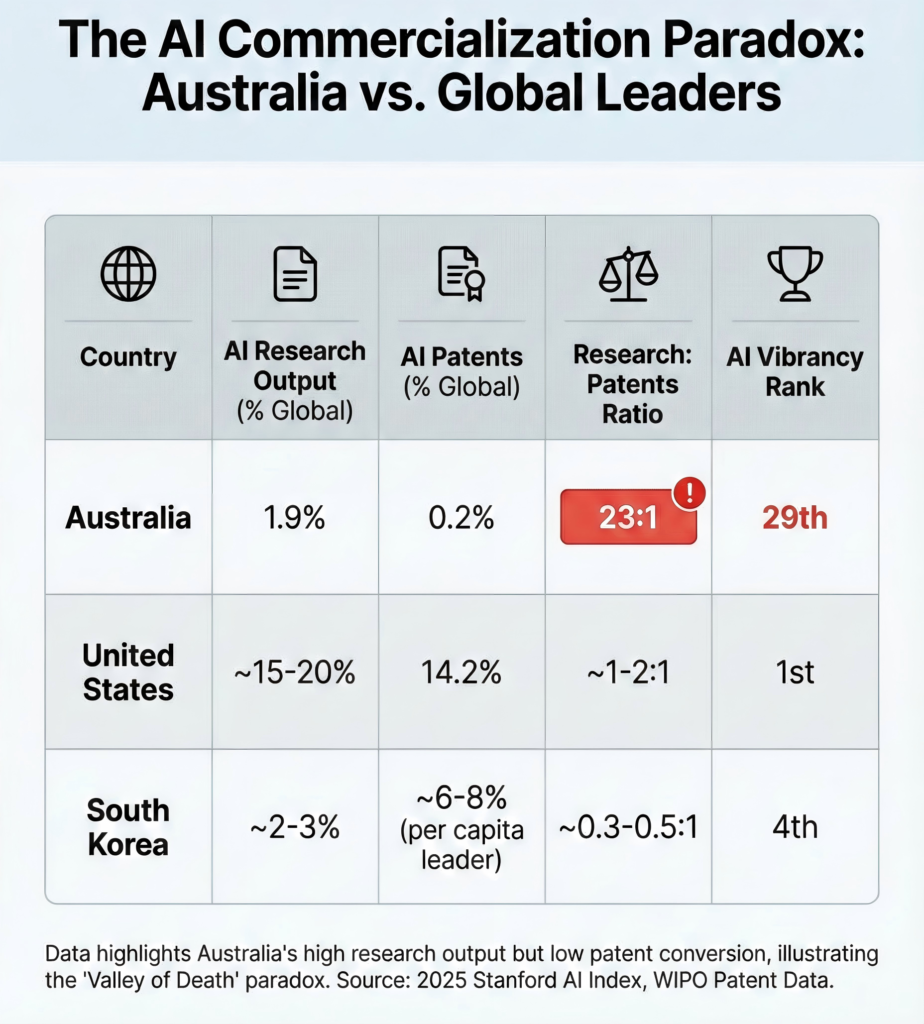

For all its academic brilliance, Australia is failing the commercialization test. The statistics are damning. While Australia produces 1.9% of the world’s AI research publications—an impressive figure for its size—it captures only 0.2% of global AI patents (Department of Industry, Science and Resources, 2025; Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, 2025).

The ratio of research papers to patents is a staggering 23:1. In simpler terms: Australian universities are doing the homework, and foreign tech giants are getting the grades.

The culprit is a lack of structural support. The Australian Securities Exchange (ASX), the nation’s primary stock market, is a relic of the 20th century, dominated by iron ore miners and the “Big Four” banks. It lacks the depth, appetite for risk, and valuation multiples to support high-growth AI companies. Consequently, the country’s best tech firms stay private or look to the Nasdaq, leaving Australian retail investors on the sidelines of their own country’s innovation boom.

Furthermore, the federal government’s response has been lethargic. While the U.S. pours billions into the CHIPS Act and AI infrastructure, and China mobilizes state resources for “sovereign AI,” Canberra has offered little beyond committees and consultation papers. The nation ranks 29th in “AI Vibrancy,” trailing developing economies like Malaysia (Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, 2025).

Visualizing the Gap: A Comparative Look at Research to Commercialization

To underscore Australia’s missed opportunities, consider this cross-country comparison with the United States and South Korea—two nations that excel at bridging the “research to commercialization” divide. Drawing from the 2025 Stanford AI Index Report and related patent data, the table below highlights key metrics: global shares of AI research output (publications), AI patents, the research-to-patents ratio, and overall AI Vibrancy rankings. These figures reveal how Australia lags in converting academic prowess into patented innovations and economic impact, while peers like the U.S. (with balanced research-patent alignment) and South Korea (patent-heavy per capita) forge ahead.

Australia’s high research-to-patents ratio signals a “valley of death” where ideas die before reaching market viability, often due to limited venture capital and policy inertia. In contrast, the U.S. benefits from Silicon Valley’s ecosystem, turning substantial research shares into strong patent outputs with near-parity ratios. South Korea, propelled by conglomerates like Samsung, punches above its weight in patents (with 17.3 patents per 100,000 inhabitants in 2023), achieving inverted ratios that favor commercialization—bolstered by government R&D incentives (Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, 2025). If Australia doesn’t reform its capital markets and amp up AI-specific investments, its innovations risk being harvested elsewhere, exacerbating the paradox.

Australia stands at a precipice. It possesses the raw intellectual fuel to be an AI superpower. But without a capital market that understands tech and a government that prioritizes innovation over excavation, Australia risks becoming the world’s AI research lab—generating brilliant ideas that are monetized by everyone else.

The Canadian Contrast: A Cautionary Foil in Embracing China’s AI and Robotics Revolution

While Australia’s AI rankings dominate those of its Commonwealth peer Canada—where even top institutions like the University of Alberta rank #53 globally in AI, far behind multiple Australian entries in the Top 20—the northern cousin is showing a bolder path forward in leveraging international ties for technological advancement. This contrast underscores Australia’s potential pitfalls, as Canada actively courts partnerships that could siphon off Down Under’s hard-won research fruits.

In January 2026, Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney signed a landmark agreement with China, slashing tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles (EVs) from 100% to 6.1% for an initial quota of 49,000 units, with expectations of rising to 70,000 over five years (Prime Minister of Canada, 2026; Reuters, 2026). The deal also anticipates significant Chinese investment in joint-venture auto manufacturing within Canada, aiming to build out EV supply chains and create jobs. This move signals Canada’s determination to embrace the AI and robotics revolution led by China, as modern EVs rely heavily on AI-driven autonomous systems, smart manufacturing, and robotic assembly lines.

China’s AI leadership is concentrated in the “Robot Belt”—a southeast coastal innovation corridor stretching from Beijing to Guangdong, home to powerhouses like Tsinghua University, Peking University, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, and Zhejiang University. Ironically, Australia’s links to this Robot Belt run deeper than Canada’s, with nearly all Australian universities in the AI Top 100 boasting collaborations with its key institutions. For instance, Monash University’s joint graduate school in Suzhou with Southeast University focuses on AI, robotics, and engineering, fostering cross-border research and talent exchange. Other ties include UTS’s joint AI labs with Chinese partners and UNSW’s Torch Innovation Precinct, which channels Beijing’s tech ecosystem into Australian projects.

This academic intimacy extends to industry: In 2025, Chinese-manufactured cars accounted for approximately 20% of Australia’s new vehicle sales, totaling around 252,702 units, with a significant portion originating from Robot Belt hubs like Guangdong (BYD’s base) and surrounding regions in the Pearl River Delta and Yangtze River Delta (carsales.com.au, 2026; Drive.com.au, 2026). Brands like BYD, Chery, and GWM, powered by AI-integrated factories in these areas, have surged in popularity Down Under.

Yet, despite these robust connections, Australia’s government enthusiasm for participating in the AI and robotics revolution lags behind Canada’s pragmatic pivot. Canberra’s caution—shaped by foreign interference laws, export controls, and alliances like AUKUS—has tempered deep tech integration with China, even as academic and market ties flourish. Canada, with less entrenched Robot Belt relationships and no Chinese EVs on sale prior to the deal, is now positioning itself as a North American gateway for Chinese-led innovation.

If Australia doesn’t accelerate its commercialization drive, its bountiful AI outputs could increasingly find homes abroad—not just in the U.S. or China, but in Canada, where open doors to Robot Belt tech might turn Australian ideas into scaled North American industries. The paradox deepens: a research giant risking irrelevance while smaller players seize the revolution.

References

carsales.com.au (2026) VFACTS: Chinese manufactured vehicles a key driver of 2025 Australia’s record new car sales result. Available at: https://business.carsales.com.au/news-room/news/vfacts-chinas-influence-on-2025-sales-result (Accessed: 21 January 2026).

Department of Industry, Science and Resources (2025) Australia’s artificial intelligence ecosystem: growth and opportunities. Canberra: Australian Government. Available at: https://www.industry.gov.au/publications/australias-artificial-intelligence-ecosystem-growth-and-opportunities (Accessed: 21 January 2026).

Drive.com.au (2026) Chinese car sales break records in Australia, but not all are on the up. Available at: https://www.drive.com.au/news/chinese-car-sales-break-records-in-australia-but-not-all-are-on-the-up (Accessed: 21 January 2026).

Prime Minister of Canada (2026) Prime Minister Carney forges new strategic partnership with the People’s Republic of China focused on energy, agri-food, and trade. Available at: https://www.pm.gc.ca/en/news/news-releases/2026/01/16/prime-minister-carney-forges-new-strategic-partnership-peoples (Accessed: 21 January 2026).

Reuters (2026) Canada, China slash EV, canola tariffs in reset of ties. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/canada-china-set-make-historic-gains-new-partnership-says-carney-2026-01-16 (Accessed: 21 January 2026).

Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (2025) Artificial Intelligence Index Report 2025. Stanford, CA: Stanford University. Available at: https://hai.stanford.edu/ai-index/2025-ai-index-report (Accessed: 21 January 2026).

U.S. News & World Report (2025-2026) Best Global Universities for Artificial Intelligence. Available at: https://www.usnews.com/education/best-global-universities/artificial-intelligence (Accessed: 21 January 2026).

·